The story of William Ohlert was first published in a magazine during the years 1888–1889[1]. Later this narrative was included in the book ›Winnetou‹[2]. In the English language edition of Karl May’s book ›Winnetou‹[3] the chapter with William Ohlert has been left out.

Karl May described William Ohlert in the story as the only son of a banker. More artistic than practical by nature, William had some poems published. In order to write a play that had a psychotic poet as the main hero, William started to read books on insanity. A change in William’s personality developed. He started to think and act as a mad poet. William composed a poem ›Night Terrors‹ – »a fearful cry of a gifted person, who fought in vain against the dark powers of insanity and felt he had to give in to them.«[4]

At this stage William had run away from home in a company of a ruthless villain whose intention was to get possession of his money. Old Shatterhand becomes a bounty hunter and catches up with William in Mexico. After William suffers a blow on his head, Old Shatterhand takes him to a member of a religious order, Pater Benito, who cures him completely from his madness. However William suffers from amnesia. He does not remember anything between the time he left home and the blow on his head. In the end William’s father comes to Mexico to take his son home.

At the beginning of his journey William Ohlert was able to take his poem ›Night Terrors‹ to the editorial office of a newspaper and paid for its publication. He also cashed money at a bank underway. We find three descriptions of William Ohlert in the story by various observers.

The lady-owner of a boarding house where Ohlert stayed noticed: »This gentleman made an impression on me of a fine, educated man, of a true gentleman. Unfortunately he did not talk much and did not associate with anyone. He went out only on one occasion, that is when he brought you the poem.«[5]

Old Death also met William Ohlert: »Pity about his companion [i.e. William Ohlert] with whom he traveled! Made an impression of a veritable gentleman, only always sad and gloomy, stared ahead as someone mentally disturbed.«[6]

To Old Death’s question: »Is this William

Ohlert then fully insane?« Old Shatterhand gives this answer: »No. I do

not understand at all psychiatric diseases. Yet I would speak here about

a Monomania, because he, except in one point, is a full master of his

mental capacities.«

»›And the more it is

incomprehensible to me [says Old Death] that he allows that Gibson such

an unlimited influence on himself. He seems to follow and obey this

person in everything. In any case he cunningly misuses the monomania of

the patient and exploits it for his purposes.‹

›Ohlert perhaps does not know at all he is being followed and that he

finds himself on the wrong path. He fully believes himself acting

correctly, lives only for his idea, and the rest is Gibson’s doing. The

confused did not think it to be unwise, to give Austin as the end of his

journey…«[7]

Later a German blacksmith described his meeting with Ohlert: »… the other one is Mr. Ohlert, who embarrassed me in a major way. He kept asking about gentlemen whom I never saw in my life, as for example about a black man called Othello, about a young Miss from Orleans, Joan with other names, who first looked after sheep and later accompanied a King into war, about a certain Mr. Fridolin, who should have made a pilgrimage to Eisenhammer, about an unlucky Lady Maria Stuart, who was beheaded in England, about a certain bell which should have sung a song by Schiller, about a very poetic gentleman called Ludwig Uhland, who cursed two singers for which some Queen threw down at him a rose taken from her bosom. He was glad to find out I was German, and brought forward a lot of names, poems and theater stories, from which I remembered only those, which I just mentioned. All this was going around in my head like a millstone. This Mr. Ohlert seemed to be quite nice and harmless person, but I could bet that he had a little kink of some kind. Finally he pulled out a sheet of paper with rhymes, which he read to me. There was a talk about terrible night, which was followed twice by morning, but which had no morning the third time. There appeared rainy weather, stars, fog, eternity, blood in the veins, a spirit crying for release, a devil in the brain and a dozen of snakes in the soul, in short, all confused staff, which is quite impossible and also does not fir together. I really did not know whether I should have laughed or cried …«

Old Shatterhand wanted to find out what

pretence Gibson-Gavilano used to take William Ohlert with him: »This

pretence must have been for the mentally sick very tempting and in close

connection with the fixed idea to write a tragedy about a mad poet.

Therefore I asked him [the blacksmith]: ›What language used this young

man during the talk with you?‹

›He

spoke German and talked very much about a grieving play, which he wanted

to write, however considered it necessary that all what should have been

in it he had to live through first.‹

›This is hard to

believe!‹

›Why not? I have a

different opinion, Sir! The madness is exactly in that, to undertake

things, which would not come into the minds of sensible persons. Every

third word was a Senorita Felisa Perilla, whom he, with the help of his

friends, had to carry off.‹

›This

is really madness, clear madness! If this man transfers into reality the

figures and events of his drama, one has to quite definitely try to

prevent this …‹«[8]

There is an interesting remark about William Ohlert that Old Death hears from Senor Cortesio: »Now he [Gibson-Gavilano] comes back with a Yankee, who wants to get to know Mexico and had asked him, to be introduced into the realm of the art of poetry. They want to build a theater in the capital.«[9]

Karl May wrote in his biography: »… the ideals … which I carried deep in my heart since my boyhood, To be a writer, a poet! To learn, learn, learn! … To get to know the world as a stage, and the mankind which moves there! And at the end of this hard, laborious life to write for the other stage, for the theater…«[10] »To write for the theater! To write dramas!«[11]

William Ohlert becomes very withdrawn during

the trip: »›Did Gibson and William Ohlert speak about their affairs and

plans?‹

›Not

a word. The first was very cheerful and the other very quiet.‹«[12]

Towards the end of the journey William Ohlert

deteriorated bodily and psychologically to an almost catatonic state:

»Gibson and William Ohlert were also sitting amongst them. The last one

looked extremely ill and deranged. His clothing was in tatters and his

hair gone wild. The cheeks were sunk in, the eyes deep in their sockets.

He seemed neither to see nor to hear what was going on around him, had a

pencil in his hand and a sheet of paper on the knee and stared down onto

it. He was without any will.

He

[Gibson] pointed at the same time at William Ohlert: ›Him? A witness

against me?‹ Asked Gibson. ›This is again a proof that you are mistaking

me for someone else. Ask him than now!‹

I put my hand on

William’s shoulder and called his name. He lifted slowly his head,

stared at me incomprehensibly and said nothing.

›Mr. Ohlert, Sir

William, can you hear me?‹ I repeated. ›Your father sends me to you.‹

His empty look kept

hanging on my face, but he did not say a word. Now Gibson interjected in

a threatening tone: ›We want to hear your name. Say it now.‹

The addressed turned

his head to the caller and answered half audibly in a frightened tone

like a shy child: ›My name is Guillelmo.‹

›What are you?‹

›A poet.‹

I

continued to ask: ›Is your name Ohlert? Are you from New York? Do you

have a father?‹ But he denied all the questions, without remembering

anything in the least.«[13]

When Karl May was arrested on March 26, 1865, he was »quite without movements and seemingly lifeless, and also, after the Police doctor was called in, [Karl May] did not talk.«[14]

Old Shatterhand had an idea: »I took my wallet out. I had the newspaper page with Ohlert’s poem in it, removed it and read slowly and with loud voice the first stanza. I believed the sound of his own poem would pull him out from his spiritual insensitivity. But he kept looking down at his knees only. I read the second stanza, also in vain. Then the third. The last two lines I read louder then the previous. He lifted his head, stood up and stretched out his hands. I continued reading. He cried out, jumped towards me and grabbed the paper. He leaned over the fire and read himself, loudly from the beginning to the end. Then he straightened up and cried out in a triumphant tone, so that it reverberated far through the night in the quiet valley: ›A poem by Ohlert, by William Ohlert, by me, by myself! Then I am this William Ohlert, I myself. Not you are called Ohlert, not you, but I!‹«[15]

Unfortunately at this stage the Indian chief

»came in a hurry, quite forgetting the council meeting and his own

dignity, pushed William to the ground and ordered: ›Be quiet – dog!

Should the Apaches hear we are here? You are asking for the battle and

death to come here!‹

William Ohlert uttered a muted cry protesting and looked up the Indian

chief with a stare. The flare-up of his mind was suddenly extinguished

again. I took the paper from his hand and put it back into my pocket.«[16]

Karl May gives us three more glimpses at William Ohlert before the great finale: »William Ohlert also sat still in his place and stared at the pencil that he again held in his fingers.«[17]

William Ohlert was writing on his sheet of paper, deaf and blind to everything else.«[18]

«He [i.e. Gibson] still stood at the fire, grabbed Ohlert by the arm in an effort to pull him up from the ground.«[19]

Finally the last drama of the story develops:

»I saw … Gibson with William Ohlert to enter. They were politely

welcomed and invited to sit down, which they did. Gibson introduced

himself as Gavilano and stated he was a geographer, who wanted with his

colleagues to visit the local mountains. He was camping near by and

there came to him a certain Harton, a Gambusino. From him he learned

that there is not far away an ordinary inhabited settlement. His

colleague is sick and so he let Harton to take him here, in order to ask

Senor Uhmann to allow his colleague stay overnight with him.

Whether this was a

clever or silly idea I did not have time to think it over. I stepped

forward from my hiding spot. When Gibson saw me he got up. He stared at

me with an expression of an utter horror.

›Are the Tschimarra

Indians also sick, who are coming behind you, Mr. Gibson?‹ I asked him.

›William Ohlert is not staying here, but is going with me. And I take

you with me as well.‹

Ohlert was sitting

as usual without participating. Gibson however took hold of himself

quickly. ›You scoundrel!‹ He shouted at me. ›Do you pursue honest people

even here! I will – – –‹

›Shut up, man!‹ I

interrupted him. ›You are my prisoner!‹

›Not yet!‹ He

replied angrily. ›Take this first!‹

He had his rifle in his hand and

lifted it to strike me with the butt. I grasped his arm. Because of that

he half turned around; the rifle butt whistled lower and hit Ohlert’s

head, who immediately fell down. The next moment some of the workers

forced their way in through the back of the tent. They pointed their

rifles at Gibson whom I was still holding.

›Don’t shoot!‹ I cried out, as I wanted to seize him alive. But it was

too late. A shot ran out and he slipped from my arm, hit through the

head, dead to the ground.«[20]

Karl May was sentenced to six weeks of detention (served from 8 September to 20 October 1862) for not returning a watch to his flatmate at X-mass in 1861. He wrote about it later: »[The events] had acted like a blow on my head, under which force I had collapsed. And how I collapsed! I stood up again, however only on the outside, in the inside I stayed down in a dull stupor, for weeks. Even months.«[21]

After William Ohlert received the blow on his head »[he] was alive, but did not want to wake up from his stupor.«[22]

The story of William Ohlert continues: »Two months later I was staying with the good monk Benito from the Congregation El buono Pastor in Chihuahua. To him, the most famous physician of the northern provinces, I brought my patient, and he succeeded to cure him fully. I say completely, because marvelously with the bodily recuperation came back also the normal state of mind. It was as if with the rifle butt blow the unfortunate spiritual Monomania, to be a mad poet, was killed. He became lively and healthy, even at times cheerful and longing for his father.«[23]

We know from Karl May’s biography that the person who played such an important role in helping May to regain his mental balance, was the Waldheim Prisons Institution’s Catholic catechist Johannes Kochta. May described him as follows: »He was only a teacher, without an academic background, but an honorable man in any respect, humane as rarely anyone else …«[24]

Ohlert suffered a true amnesia[25]: »… one has indeed to admit that a true miracle had happened. Ohlert did not want to hear anymore the word ›poet‹. He could remember every hour of his life. The time from when he ran away with Gibson until his final waking up at the Bonanza represented a completely empty page in his memory.«[26]

The very end of the story: »A servant knocked,

opened the door and let in a gentleman. When William saw him he cried

from joy. What pain and worries he caused his father, he knew really

only from me. He threw himself crying into his arms. We however left

quietly.

There was time later to talk it all over and tell everything. The father

and son were sitting hand in hand alongside.«[27]

When Karl May was released from Waldheim prison on the 2 May 1874, it was his father who came to him: »Father came to meet me. Even now he did not think about making any reproaches.«[28]

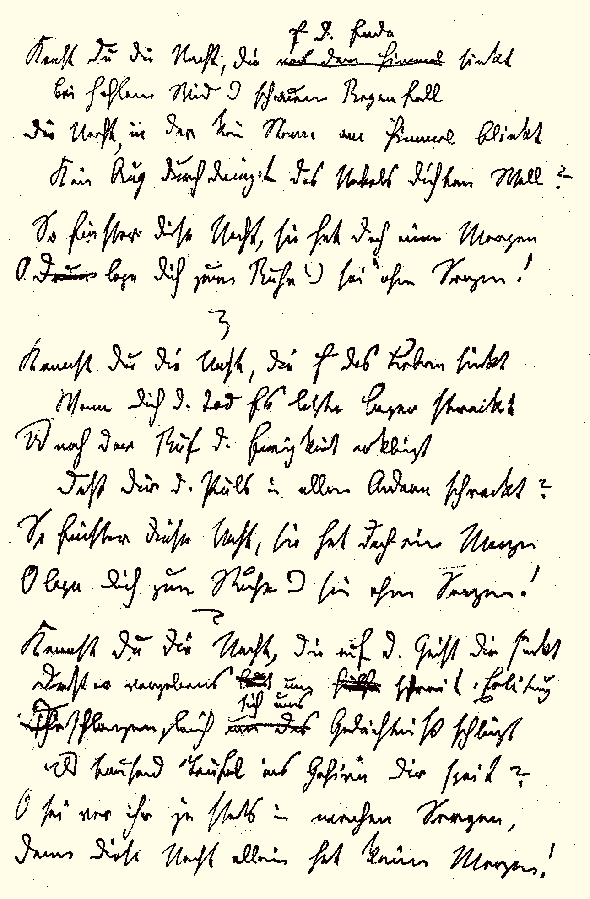

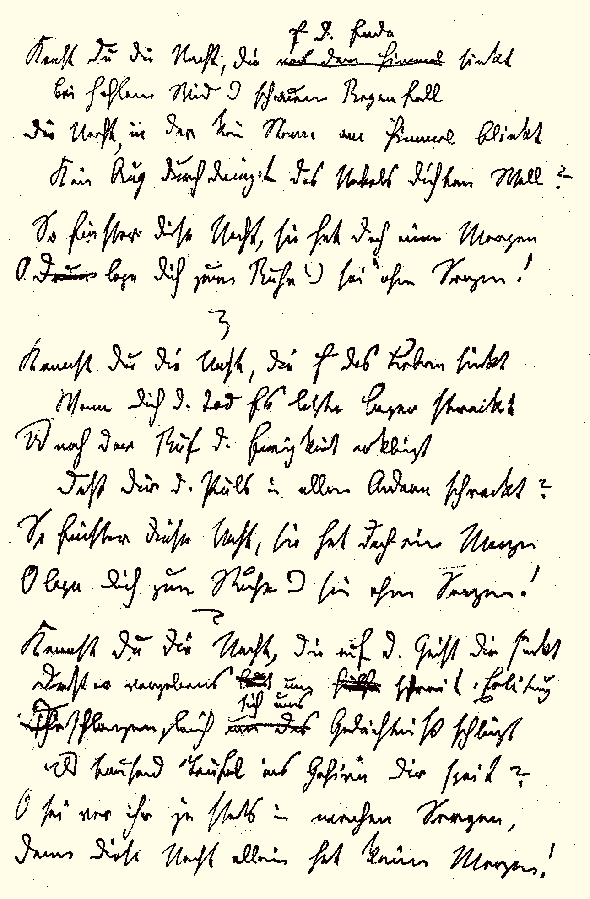

The poem »Night Terrors« plays an important role in the story:

| ›NIGHT

TERRORS‹

Do you know the

Night, descending on Earth, Do you know

the Night, descending on Life, Do

you know the Night descending on your Mind, |

The poem ›Night Terrors‹ is one of the earliest Karl May’s poetry. It

could have been written as early as in late autumn of 1863[30]. The

handwritten original has no title and differs from the published version

in the third line of the third stanza. Instead of the original ›into

memory‹[31] the printed version gives ›around the soul‹.[32]

The primary version presents a leading symptom

– amnesia, loss of memory. This was indeed in 1863 one of the main

disturbances Karl May suffered from.[33] The other symptom was hallucinations,[34] also

poetically expressed: »And a thousand demons spit in your brain.«[35]

The »Monomania«

The diagnosis Karl May made on William Ohlert’s state of mind was ›Monomania‹.[36] Karl May also stated that William »is a full master of his mental capacities.«[37]

It is of interest to note how Karl May described his own mental state from 1864: »I was sick in my soul, but not in my mind. I had the capability to reach logical conclusions, to solve every mathematical problem.«[38]

Monomania is a term no longer in use. It used to describe a psychosis characterized by thoughts confined to one idea or group of ideas, an inordinate or obsessive zeal for or interest in a single thing, idea, subject, or the like. A mental disorder especially when limited in expression to one idea or area of thought. The old psychiatric textbooks classified for example Pyromania, Kleptomania, and some impulsive sexual aberrations as monomania.[39] [40]

What was than the Monomania diagnosed by Karl May?

From the four main psychoses – Schizophrenia, Paranoia, Depression and Bipolar Syndrome – in the case of William Ohlert schizophrenia should be considered. Also an acute and transient Psychotic Disorder could not be excluded.

William Ohlert demonstrated evidence of perceptual abnormality or thought disorder – indicating possible psychotic illness. His appearance, at the beginning clean and neat, deteriorated during the journey. Behavior, detached first, became retarded. Conversation, after the initial flood of thoughts during the discussion with the blacksmith, flat or nonexistent. Affect and mood turned into depression. He did not seem to be dangerous to himself or other people. He had no insight into his condition and no judgment of the situation.

Schizophrenic symptoms typically emerge at the age of 20 or early 30. Symptoms are highly variable. Agitation and distress, catatonic state, i.e. trancelike, immobile, unresponsive condition, are quite common. Patients are out of touch with reality or unable to separate what is real from what is unreal. They often hallucinate and suffer from delusions. There is a disorder of thinking. Speech, attentiveness, behavior and thoughts become disjointed, without logical sequences. Schizophrenia causes a slowly progressive deterioration of the ability to function, occupationally and interpersonally.

If Karl May had suffered from schizophrenia, he would not have been able to write the books as he did. His personality would disintegrate.

Acute and transient psychotic disorders are similar in appearance to acute episodes of schizophrenia. Hallucinations, delusions, and other symptoms of schizophrenia are usually most prominent and there may be fluctuation in emotional state. There is an acute onset of symptoms, and the course of the disorder is brief. If symptoms endure for longer than one month, the diagnosis should be changed to something more appropriate, as schizophrenia or delusional disorder. Recovery is usually complete within two or three months, and often within a few days of weeks.

Ohlert could not have been hypnotized by Gibson-Gavilano, because he started to identify himself with the mad poet of his play before he met him.

There are similarities between William Ohlert of the story and the course of events in the life of Karl May. We can therefore assume that Karl May described in William Ohlert autobiographic elements of himself.

A diagnosis of a fugue, dissociative amnesia, stupor, trance and identity disorder could be made in William Ohlert.

There is a scene in the Ohlert’s story, when he responds to Old Shatterhand reading to him the poem. This reminds of coming out from Dissociative Stupor.[41] [42] In Ohlert’s case it was cut short and reverted by the brutal interference of the Comanche Indian chief.

If we look at William Ohlert in a broader context of ›Karl May – the Person‹, then we can recognize that May had described in the story elements of his mental condition.

The poem ›Night Terrors‹ by Karl May, composed not such a long time before the story of ›The Scout‹ was written speaks of Amnesia and Hallucinations. The handwriting itself suggests May’s disturbed state of mind. The way William Ohlert left home is what we know nowadays as the Fugue – sudden, unexpected travel from home or work, with inability to recall some or all of one’s past. Karl May described a fugue in his biography. William Ohlert did this in an Altered State of Mind – as an Alter – convinced that he was the mad poet of his play. The fact that Karl May suffered from amnesia concerning some events in his early life is stated not only in his biography, but also by other observers.

The Complete Recovery – in Karl May’s words a »true miracle«[43] – from William Ohlert’s mental state with the help and assistance of Pater Benito, relates to May’s stay at Waldheim, where he served his second prison term from 3 May 1870 till 2 May 1874. It was at Waldheim where May met his Psychotherapist, the Prison Roman Catholic catechist Johann Kochta. May’s father came to collect him on release, just as William Ohlert’s father traveled to his son.

What is missing to make a firm diagnosis of Dissociative Identity Disorder (D.I.D.) in the narrative is the childhood trauma. There is no mention of it in the William Ohlert’s story. We know that Karl May’s blindness as a child together with his father abuse represented the trauma. Of course during Karl May’s life time that connection and the diagnosis of D.I.D. did not exist.

The William Ohlert’s story is a valuable piece of

Karl May’s autobiography. It also seems to confirm that it was the

Dissociative Identity Disorder Karl May suffered from between the years

1862 and 1874.

I thank Mr. Ralf Harder for kindly pointing out to me the importance of the Karl May’s poem ›Night Terrors‹, and making me aware of other important study materials.[44] [45]

Please click on the hyperlinked reference numbers to return to your place in the text.

[1] Karl May: ›Der Scout‹, in: Deutsche Hausschatz

XV. Jg. (1888–1889); Reprint: KMG ›Hausschatz‹ 1997.

[2] Karl

May: ›Winnetou II‹, Zuercher Ausgabe, Amerika Band 9, Zurich 1996,

pp.9 – 339. [All quotations come from this edition, as it follows the

magazine text from the years 1888–1889.] First book edition of

›Winnetou‹ appeared in 1893.

[3] Karl May: ›Winnetou‹, The Seabury Press, New York 1977.

[4] in [2], p.36.

[5] in [2], p.37.

[6] in [2], p.50.

[7] in [2], p.52.

[8] in [2], p.98.

[9] in [2], p.111.

[10] Karl May: ›Mein Leben und Streben‹, Olms Presse New York 1997, p.107.

[11] in [10], p.112.

[12] in [2], p.208.

[13] in [2], pp.242-250.

[14] Wohlgschaft, H.: ›Grosse Karl May Biographie‹, Igel Verlag 1994, p.94.

[15] in [2], pp.251-253.

[16] in [2], p.253.

[17] in [2], p.257.

[18] in [2], p.265.

[19] in [2], p.269.

[20] in [2], p.269.

[21] in [10], pp.109-110.

[22] in [2], p.336.

[23] in [2], p.337.

[24] in [10], p9.172-173.

[25] Retrograde amnesia after a head injury as a rule is shorter and does not involve such a long time period.

[26] in [2], p.337.

[27] in [2], p.338.

[28] in [10], p.178.

[29] The Karl May’s original handwritten text appeared in KMG Jahrbuch 1971, p.123. The German original ›Die fürchterlichste Nacht‹ is in (2) p.35.

[30] Ralf Harder: Karl-May-Biography

[31] »ins Gedaechtniss«

[32] »um die Seele«

[33] in [10], p.107.

[34] in [10], p.112.

[35] »Und tausend Teufel ins Gehirn dir speit«

[36] in [2], p.52.

[37] As in above: »… vollständig Herr seiner geistigen Tätigkeiten ist.«

[38] in [2], p.111.

[39] Zetkin, M.: ›Woerterbuch der Medizin‹, VEB Verlag Berlin 1956, p.571.

[40] Kufner, K,: ›Psychiatrie II.‹ Praha 1900, p.334.

[41] Brief Dissociative Stupor (BDS) is proposed as a new category into the DSM-IV (Alexander PJ, Joseph S., Das A.: ›Acta Psychiatr‹, Scand. 95(3):177-182,1997.)

[42] DSM-IV: American Psychiatric Association: ›Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – fourth edition‹, Washington DC, 1994, USA.

[43] In [2], p.337.

[44] Roxin, C.: Introduction in ›The Scout‹, KMG ›Hausschatz‹ Reprint 1977, p.3.

[45] Lorenz, C.: In KMG-Jahrbuch 1982, p.138 ff.